2026 . . . multimedia: digital images, synthesized music . . . 15 min.

The images are digital photos abstracted to explore their vivid colors and natural shapes. The color spectrum arranges hues from what may be considered metaphorically cool (indigo/blue) to hot (red). The spectral order for frequency of light waves is the same reversed, slowest (red) to fastest (indigo).

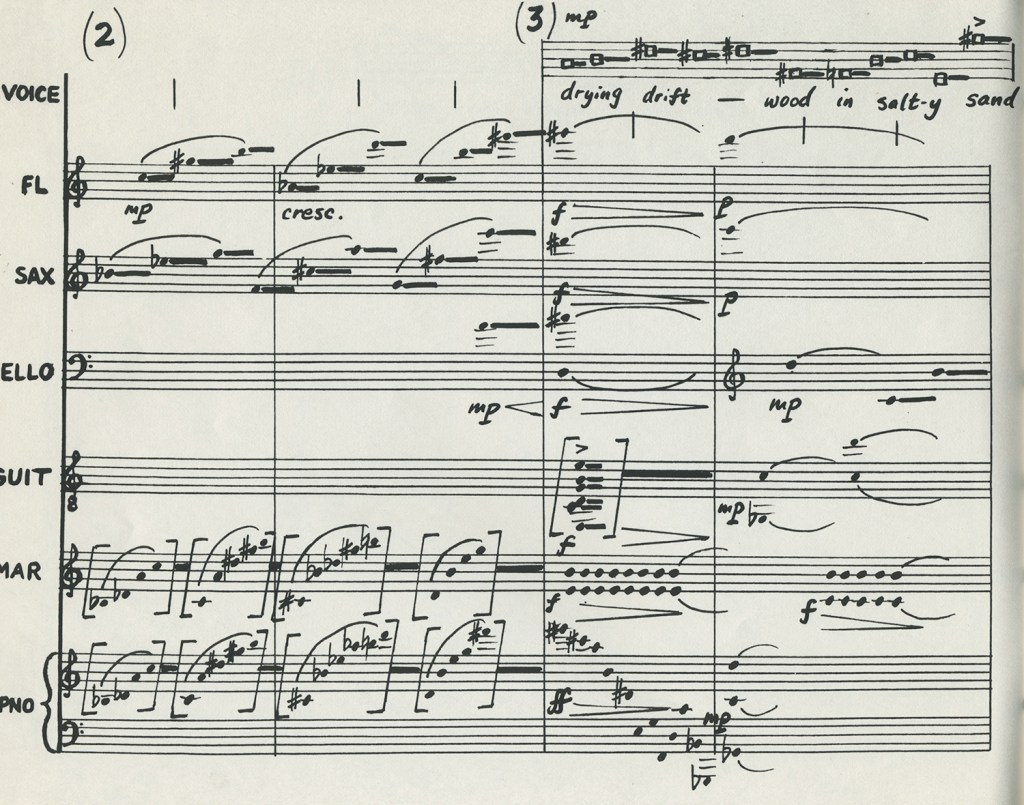

Sounds are tone clusters (adjacent steps of a common pitch scale sounding simultaneously instead of successively). The clusters contrast in timbre (sound color) and in harmonic complexity, ranging from complex dissonance (metaphorically red on the spectrum) to simpler, purer sounds (blue end of spectrum).

Watch the videos on YouTube:

“SPECTRAL SOUND“ podcast

Listen to audio only:

Clouds of sound emerge, pulsate, sparkle, and fade.

Images become geometric. Tone clusters accumulate in large tides and smaller waves, they dance and dissipate.

Geometric swatches of color cluster together like quilts. Combinations morph kaleidoscopically into one another.