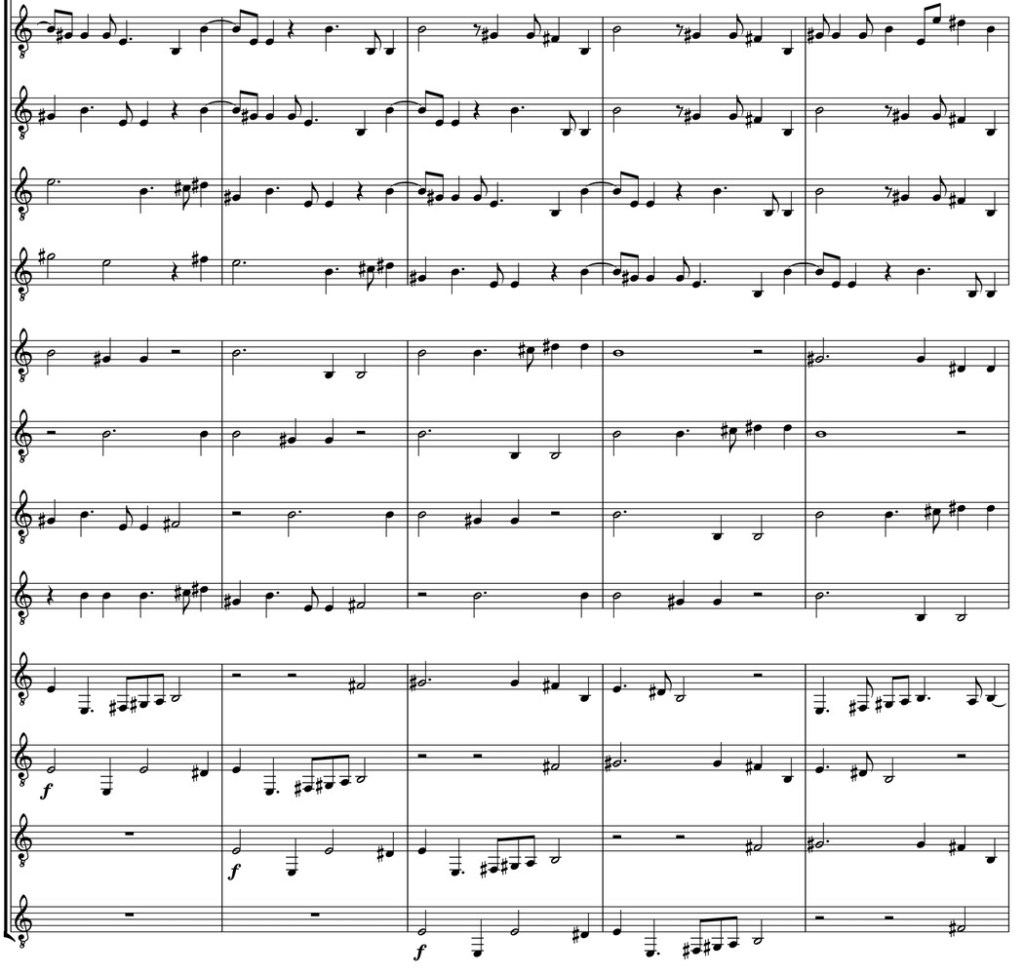

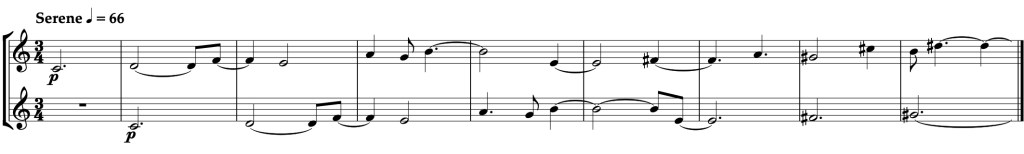

2020 . . . . trombone or euphonium and piano . . . . duration: 7:50

Peaceful Spring Lake and the San Marcos River flow from ancient springs emanating up from the Edwards Aquifer in the Texas Hill Country. For centuries, Native American tribes considered these powerful springs a sacred place where they worshiped eternal spirits. In the 20th century, the springs became the centerpiece of a famous recreation resort, Aquarena Springs. Now that the park has been restored to its original natural habitat, it remains a place of beauty and spiritual contemplation.

The main tune of Sacred Springs is based on a 15th-century English carol, a graceful tune that became the melody for the lyrical modern hymn, “O Love, How Deep.” The melody’s canonic treatment, both in somber chant and spinning ostinato, continues my modern obsession with that ancient musical technique.

To request performance materials, email the composer, tc24@txstate.edu.