Having begun composing in 1963, I started formal composition study in 1968 at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. American composer Eugene Kurtz, based in Paris but filling in that semester at Michigan, was assigned to teach the new freshman. A proponent of modern French music, his compositional models included Debussy and Ravel.

Sonatine

Kurtz assigned me to immerse myself in deep study of their music, in particular Ravel’s Sonatine (1905).

Fifty years later in my career as a more experimental composer, my compositional style began to mellow toward this gentler Impressionistic approach and a lush, bright harmonic language reminiscent of Debussy and Ravel.

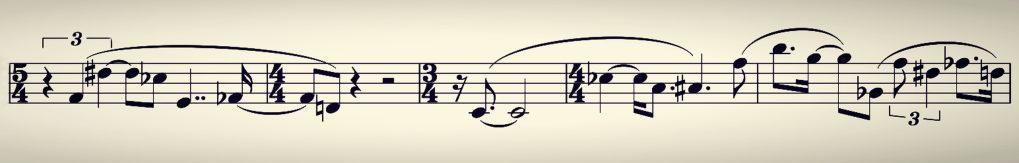

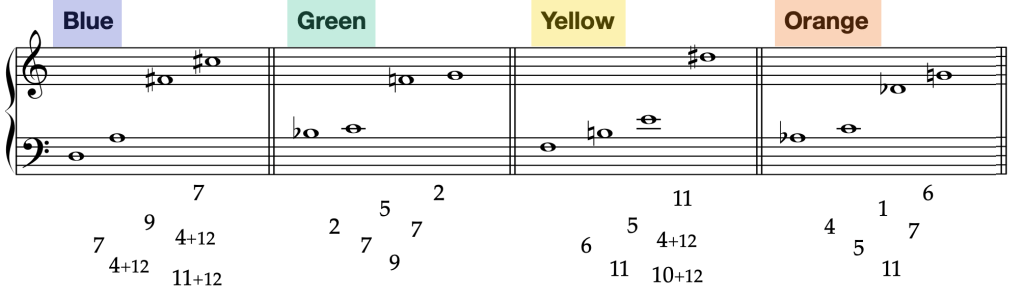

An Homage to Ravel, my new Sonatine is spun from a single harmonic progression, seven chords each stacking a Perfect Fifth interval high above another.

This material (what Schoenberg would call a Grundgestalt) generates melodic lines and many arpeggiation patterns, in successive variations of changing register, intensity, and rhythmic pace.

Clark 2025 (TC-00)

Nocturnes

In 1907, French composer Claude Debussy wrote, “I am more and more convinced that music, by its very nature, is something that cannot be cast into a traditional and fixed form. It is made up of colors and rhythms”. Color, light, and texture were also the hallmarks of a new style of painting developed by French artists — Impressionism.

At the threshhold of the 20th century on 15 December 1899, Debussy completed the first of his Impressionist masterpieces for orchestra, Trois Nocturnes. He avoided labeling it “symphony” or “tone poem” by calling the movements “three symphonic sketches”. The first sketch of Nocturnes is subtitled “Nuages,” premiered on 9 December 1900 in Paris.

Debussy’s biography describes the genesis of the piece while crossing the Pont de la Concorde in Paris in stormy weather. The composer’s notes say, “‘Nuages’ renders the immutable aspect of the sky and the slow, solemn motion of the clouds, fading away in grey tones lightly tinged with white.”

Vienna Philharmonic on Youtube

Adopting the French language and musical style recognizes the early French explorers of the Great Lakes region of North America. The first decades of my life began there in Michigan’s Lower Peninsula (the “mitten”). It has its own smaller Leelanau Peninsula in the northwest corner (the mitten’s “little finger”) near Interlochen’s National Music Camp, where I spent many summers. Nearby Grand Traverse Bay has its own even smaller Old Mission peninsula, where I loved to visit its lighthouse. The Leelanau has a grand lighthouse at its northern tip and a scenic drive, state highway M21, winding for 64 miles all the way around the peninsula’s shoreline, through forests and past the Great Sleeping Bear Sand Dunes.

In 1984 my piece titled PENINSULA for piano and sound synthesis was a more experimental work that traced a map of the Leelanau and its landmarks to determine by their spatial coordinates the timing and pitches of sound constellations.

Moving forward from that mapping phase of my compositions, my Impressionistic phase produced the sound sculpture Leelanau Sketches in 2022. Some of its musical material reappears now in five symphonic sketches, Belle Péninsule. Here is the fourth movement, which quotes Debussy’s “Nuages.”

La Mer

Debussy’s completed his second composition of three symphonic sketches for orchestra, La Mer, in 1905. It is a monumental work of Impressionist sound-painted textures and a textbook model of lush, beautiful orchestration. The three sketches are titled:

“De l’aube à midi sur la mer”

“From dawn to midday on the sea”

“Jeux de vagues”

“Play of the Waves”

“Dialogue du vent et de la mer”

“Dialogue of the wind and the sea”

My homage to La Mer, Sea Sketches, sound-paints waves, deep currents, wind, and sun-sparkling surfaces, employing swelling sound colors and post-modern cyclic techniques in a pan-diatonic tonal setting. The end briefly quotes the opening arpeggio of Debussy’s “La fille aux cheveux de lin” (“The Girl with the Flaxen Hair”) from Book I of his Préludes for piano (1909-1910).

Clark 2023 (TC-132)