In notes on a recent composition, Frost Serenade, I described “changing tonal temperature.” Here is a deep dive into what that meant.

The metaphor of tonal color and temperature has to do with what we normally call consonance and dissonance in a chord or other harmonic entity.

Centuries-old tradition classified musical pitch-intervals as pure, perfect consonances (“Perfect Fifth” and “Perfect Octave” for example); major or minor (exp. “Major Third” or “minor Sixth”); or problematic (“Augmented Fourth” and “diminished Fifth”). Some major and minor intervals (thirds and sixths) were considered imperfect consonances; the others (seconds and sevenths) were considered dissonant. Every music student learns these categories while studying 16th-century model counterpoint.

Using the color spectrum in temperature order:

Let’s convert the consonance/dissonance concept to think of a pitch-interval’s acoustic complexity. Every musical tone has a fundamental pitch, plus faint overtones that give the sound its color. They are of fading intensity and felt (as color) more than actually heard as the distinct pitches they are. Discovered by Pythagoras as partial vibrations in whole-number fractions, the overtones are always in a fixed interval ladder rising from the fundamental: Up an octave, then a Perfect Fifth, then a Perfect Fourth, a Major third, minor third, then to the eccentric seventh partial, which is out of tune by our scale-trained pitch perception (and shown a darker gray below), and on to the eighth partial, which is three octaves above the fundamental. (An octave is a multiply-by-2 operator, so partials 2, 4, 8, and 16 of the C overtone series are also the pitch-class C. Likewise, partials 3, 6, and 12 are all octave related.)

Two different fundamental pitches sounding together each bring into the acoustical mix their distinct overtones. The overtones from one either match (simple) or clash with (complex) overtones of the other. This is what makes the sonic complexity or perceived purity of the interval between two fundamental pitches. Using this relationship, we theorize that the higher we need to go to start finding matching overtones between the two pitches, the more complex is the interval. Following this logic, here is an overtone-match analysis of all harmonic intervals smaller than an octave.

PERFECT CONSONANCES

The rather pure Perfect Fifth interval between fundamental pitches, C up to G, matches overtones at G’s partial 2, a low level in the series, matching the C’s partial 3. The interval makes four such matches in this lowest-two-octaves span. The pitch match up of the G’s 2nd partial with the C’s 3rd partial (both are the same pitch, G) will be duplicated in all higher octaves, making this an acoustically simple interval. The two pitches’ overtones mostly match and don’t interfere with each other much.

IMPERFECT CONSONANCES

The triadic consonant Major 3rd interval between fundamental pitches, C up to E, matches overtones at a somewhat higher level in the series, partial 4, and makes two matches in this lowest-two-octaves comparison.

DISSONANCES

The dissonant minor 7th interval between fundamental pitches, C up to Bb, matches overtones makes only one match in this lowest-two-octaves comparison, at partial 5. That means its harmonic quality is more complex, with most of the lower overtones interfering, not matching. Not a strong dissonance, but more complex than the others.

By contrast, with the more complex Major Seventh interval (ex. C up to B), you have to go all the way up three octaves to the B’s 8th partial (matching the C’s 15th partial!) to find an overtone that matches and doesn’t conflict/interfere. The Major 7th interval can be considered much more complex at a rating of 8 than a Perfect 5th at rating 2.

The most complex interval analyzed, the minor 2nd, clashes all the way up until the 15th partial.

Summarizing the analysis with a complexity rating number for each interval:

minor 2nd = 1 semitone

15

Major 2nd = 2 semitones

8

minor 3rd = 3 semitones

5

Major 3rd = 4 semitones

4

Perfect 4th = 5 semitones

3

Augmented 4th = 6 semitones

10

Perfect 5th = 7 semitones

2

minor 6th = 8 semitones

5

Major 6th = 9 semitones

3

minor 7th = 10 semitones

5

Major 7th = 11 semitones

8

Now we can add up the ratings of each interval in a chord and take an average complexity quotient. And we can think of complex as darker than simple, or we can invoke the color spectrum. In digital photo imaging, we use a temperature metaphor, seeing red as warmest (infrared heat) down through orange, yellow, green, down to blue, the coolest. The “hottest,” most complex harmonic interval is the minor 2nd. The “coolest,” purest (other than the octave) is the Perfect 5th.

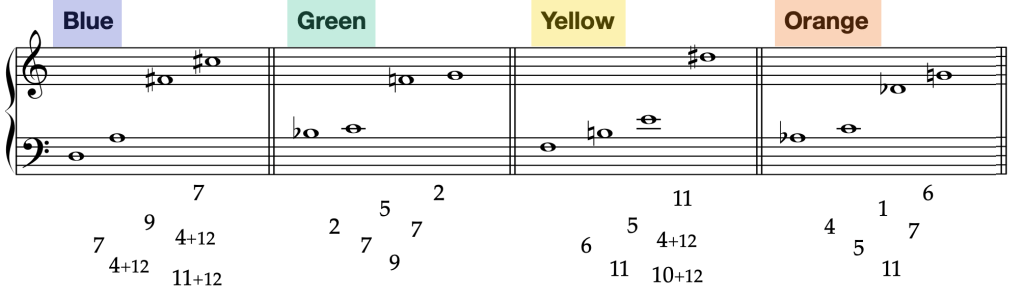

The intervals in the following example are shown in semitones. Each chord has four pitch classes and six intervals between them. The Blue chord has an average complexity rating of 3.8. Green chord is slightly more complex, at 4.3. Yellow, which includes the more complex 11-semitone Major 7ths, rates 5.5. And Orange, with the only minor 2nd 1-semitone hot dissonance, is warmest at 6.2. Try to hear the differences. (No attempt here to demonstrate a red-hot cluster mashup of pitch!)

Here is a little demonstration phrase using those four chord types to build a progression of tonal temperature colors. Again, as you listen, try to feel the temperature warm up then cool back down.