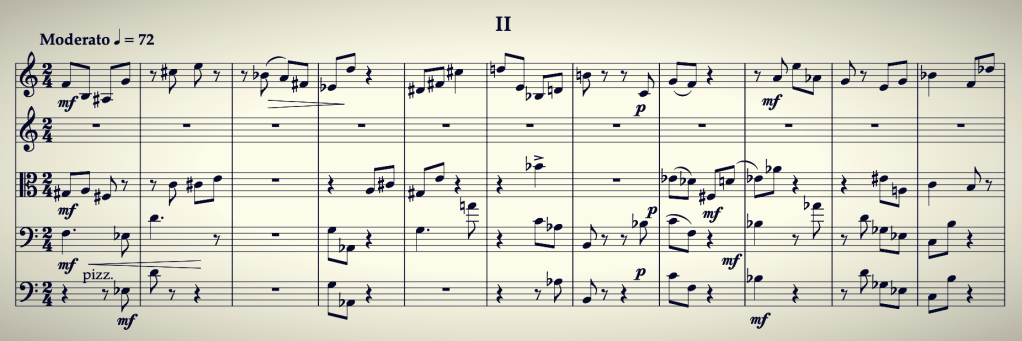

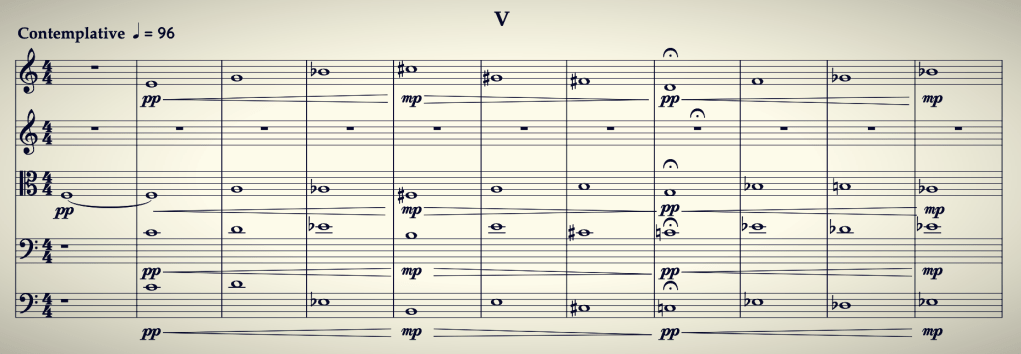

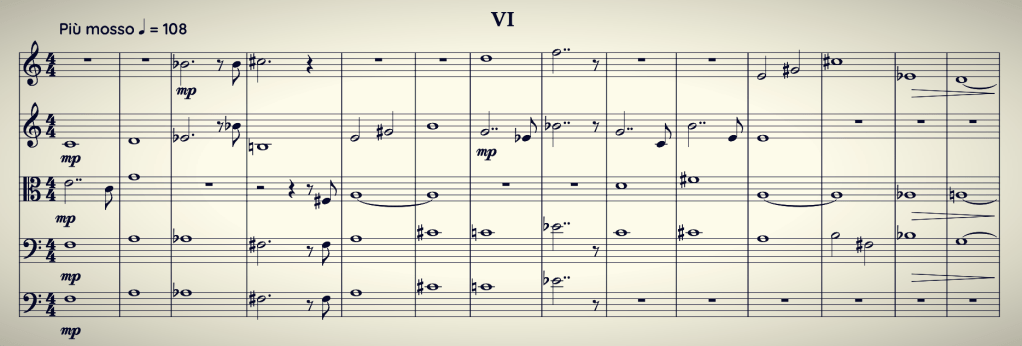

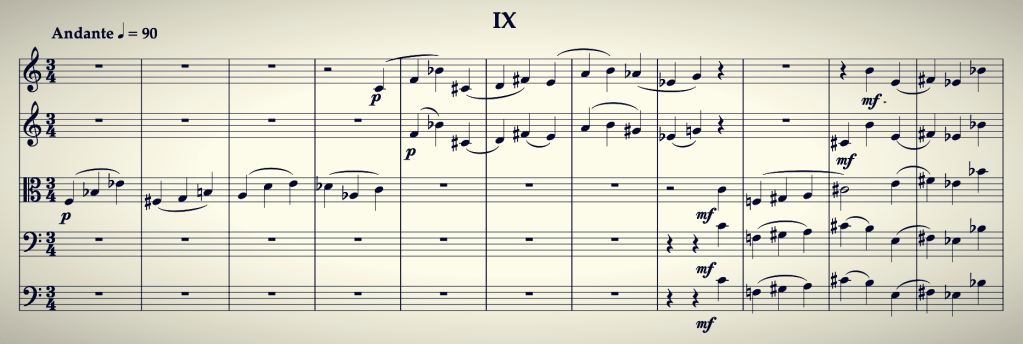

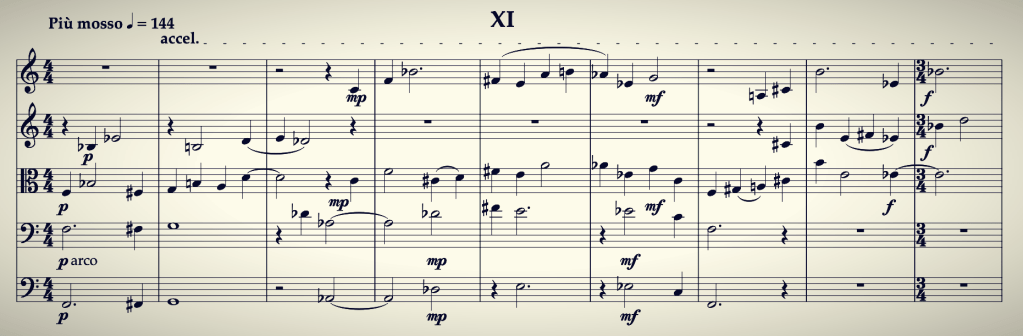

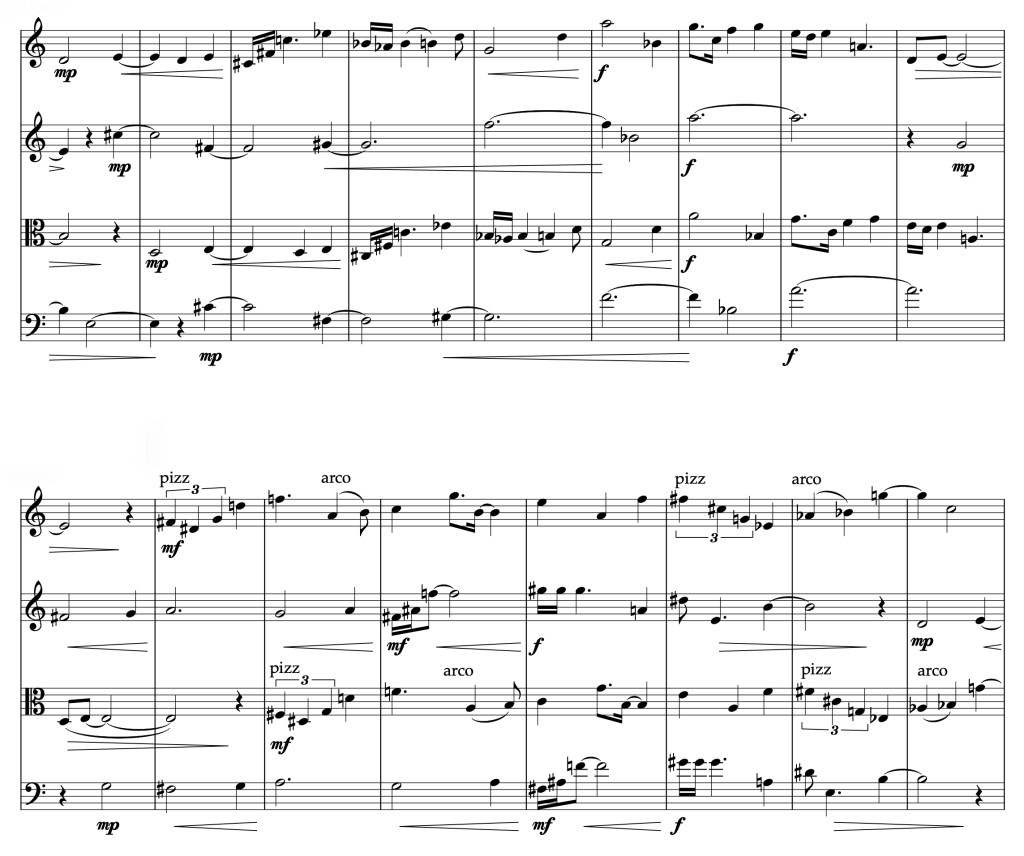

2025 . . . 17 wind/perc. instruments . . . 6 minutes

Three pieces of the early 20th century, which I studied deeply in the 1970s and later used extensively in my teaching of modern music, were each masterful explorations of musical sound color:

- Claude Debussy’s La Mer (1905), an iconic tone poem of Impressionistic musical painting with an orchestral palette

- Arnold Schoenberg’s “Farben (Summer Morning by a Lake: Chord-Colors”, the third of his Five Pieces for Orchestra, Op. 16 (1909) — a gentle study of orchestral sound color

- Anton Webern’s Symphony, Op. 21 (1928), whose first movement is a delicate gem of pointillistic color canon built on one enormous, static, symmetrical 13-pitch constellation

After fifty years, these works are embedded more deeply than ever in my musical consciousness. Farben pays special homage to Schoenberg’s masterpiece, layering kaleidoscopic wind-instrument colors to build massive, morphing constellations, echoing Webern’s hidden chord-color symmetry.