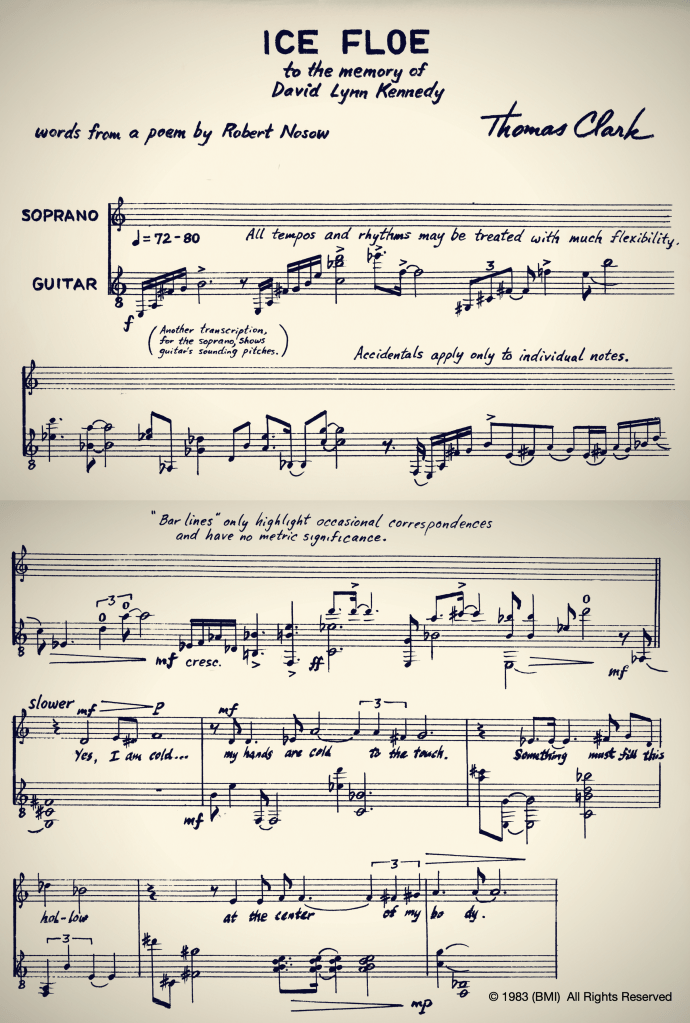

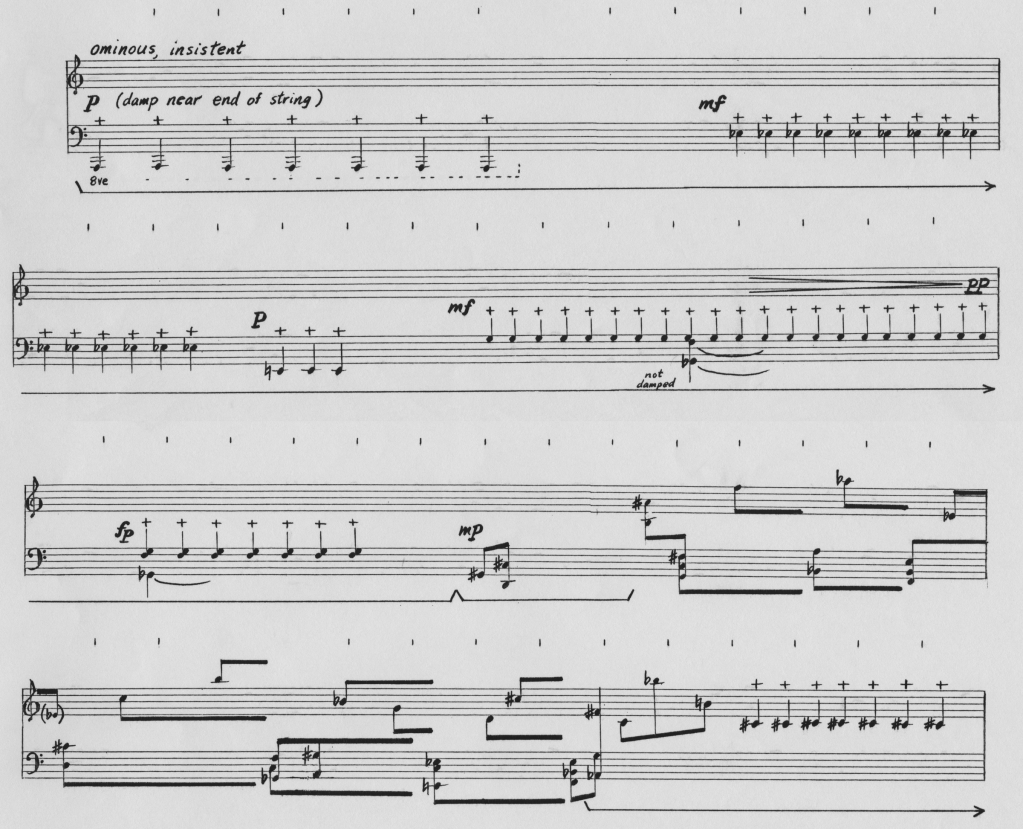

These are a distillation of my guiding principles through many years of teaching, serving as an academic leader, and meeting, working with, and understanding many very successful musicians. They don’t really belong on this composer-and-photo-art site. Or do they?

Clark’s Rules for Musician Success

Teaching is not so much imparting knowledge as it is facilitating learning. A teacher is an enabling coach on the sideline; all the on-field action is by the student, the learner. From a veteran coach, here is a simple but effective playbook.

Each rule is a command to action.

Rule 1: SHOW UP.

Music is a team sport, and the team depends on you being there every time.

Rule 2: PAY ATTENTION.

Don’t just watch and listen — think about what you see and hear.

Rule 3: DO THE WORK.

Just enough? No, all there is to do.

Rule 4: JOIN A TEAM.

Commit to the team’s success as your own.

Rule 5: PLAN AHEAD.

Essential to accomplishing Rules 1 and 3.

Rule 6: BECOME A LEADER.

It’s a lifelong process of self-development, not a hat you can simply put on.

Rule 7: ENCOURAGE OTHERS.

Part of Rule 4, this is what it means to be a humane human.

Feel free to quote and pass them on!

The original Clark’s Rules for Musician Success above are basic principles to live by, originally posted in my Texas State School of Music Director’s DIARY on January 16, 2017 . They have worn well, largely drawn from my observation of the common traits of great musicians I’ve had the good fortune to meet or work with.

Clark’s Rules for Good Leadership

As I headed toward the end of my administrative career, I reflected also on the many wonderful leadership mentors I’ve had the honor to work with, especially Dave Shrader. My reflections, incorporating a few of the first 7 rules, were posted in Director’s DIARY on . We start by repeating Rules 5 through 7:

Rule 6: BECOME A LEADER

Whatever you endeavor to lead, it’s a lifelong process of self-development.

Rule 5: PLAN AHEAD

Fundamentally, that’s the main thing a leader does.

Rule 7: ENCOURAGE OTHERS

Enable their good ideas. Trust their skill and commitment. Seek the best in others.

Rule 8: IDENTIFY GOALS

Embrace a true mission. Let the practical goals flow from the mission.

Rule 9: TAKE RISKS

Take calculated, reasonable risks worth the payoff. Don’t be afraid of failure. Redefine it as simply not succeeding on the first try.

Rule 3: DO THE WORK

Not everything can or should be delegated. Be well informed. Know how the systems and teams you lead operate.

Rule 10: SOLVE PROBLEMS

Not necessarily quickly. Sometimes with time they solve themselves. Wait while seeking all the information, possibilities you need to consider. For the toughest, brainstorm, think the unthinkable. Engage others in the solution.

Rule 11: ACT ETHICALLY

Be considerate but honest. Avoid being unnecessarily judgmental. Transcend stereotypes. Don’t assume you know what’s best for others. Choose the greatest benefit for the greatest number of stakeholders, while being fair to all.

Rule 12: SHARE CREDIT

Or just simply give it away. It will come back to you if it’s deserved. Everyone knows anyway, the best accomplishments are team collaborations.

Since 12 is to me an almost magical number, I think I’ll stop . . . for now.