2022 . . . digital sound sculpture (7 minutes)

Composed after reading Ed Viesturs’ book, No Shortcuts to the Top, his first-person account of the successful quest to climb to the summits of the 14 tallest mountains in the world, all taller than 8,000 meters (26,247 feet) above sea level. My most vivid personal and photographic experience with glacier-topped mountain ridges includes several visits to Rocky Mountain National Park, where the Continental Divide rises to a spectacular ridge of 12,000-ft. peaks beside 14,259-ft. Long’s Peak. My son Owen and I once hiked to the summit of 12,234-ft. Flattop Mountain — less than half the elevation of Viesturs’ 8,000 meters. As its name suggests, Flattop’s summit is not dramatic but connects with the string of ridges between spectacular Hallett Peak (center of photo) and Otis Peak (left of Hallett).

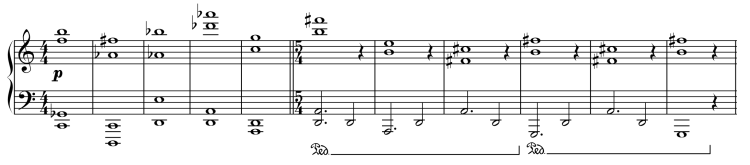

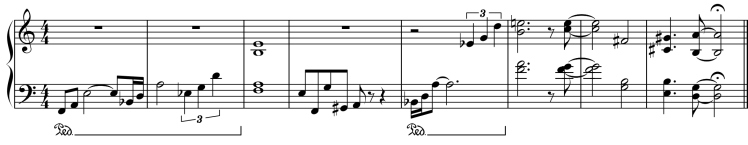

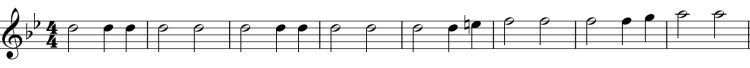

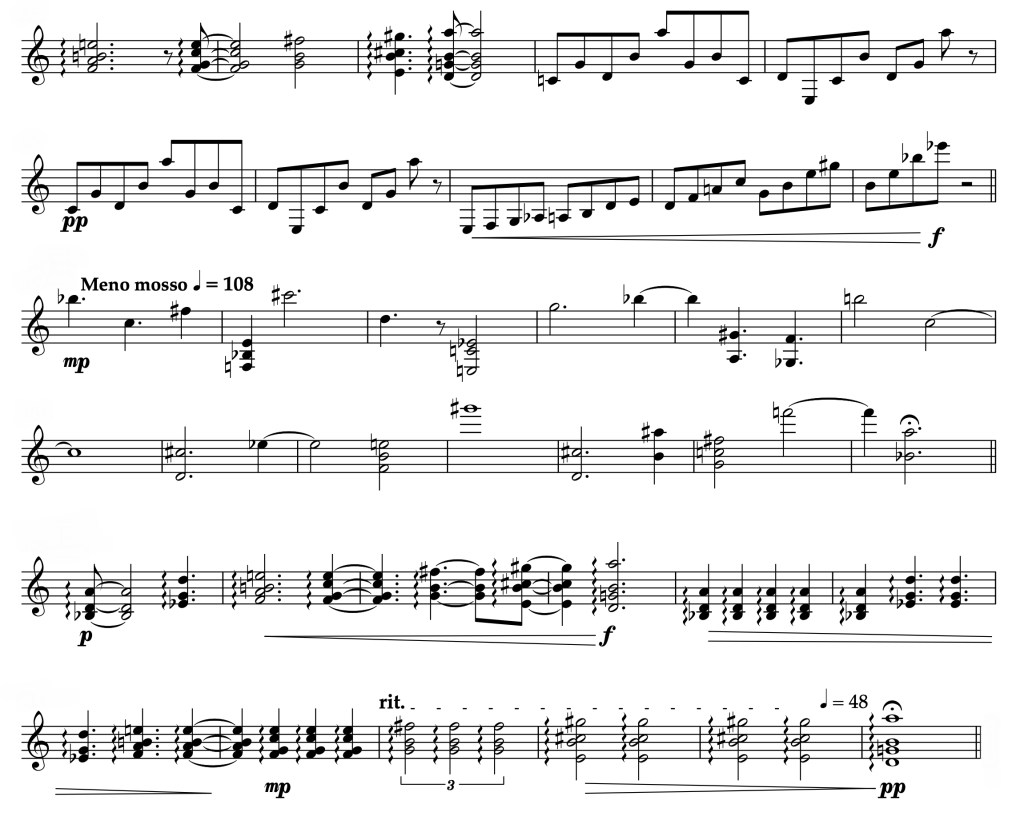

Musical patterns are all based on constellation streams of four complex 8-pitch interval arrays, as explained in Mapping the Music Universe. The chords are first presented as tall monolithic blocks separated by silence in the style of Morton Feldman:

Then they become rhythmically steady arpeggios, constantly repeating in the style of John Adams. Out of this continuous ridge of arpeggios emerge the individual pitches of the four sonorities, rising to sonic summits.

Other majestic mountain ridges I’ve admired include the Sierra Madre Oriental Mountains on the southwestern horizon of Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico, as seen from the Macroplaza. Then there is the Blue Ridge Mountains in North Carolina, where we once lived just an hour from the scenic Blue Ridge Parkway. Neither as high as the Rockies, both these sloping ridges change their deep blue hues with clouds and the sun’s progress through a day. Finally, though the Texas Hill Country is not really mountains at all, we live on its eastern edge on a road named Summit Ridge Drive.